Summary of the talk that Jon Agar (UCL) gave at Cabinet on the 3rd March

The Sixth Extinction – the global, human-caused mass extinction of animals and plants – is one of the greatest environmental crises of the modern world. What I addressed in this talk was the mobilisation of quantitative science in response to this crisis.

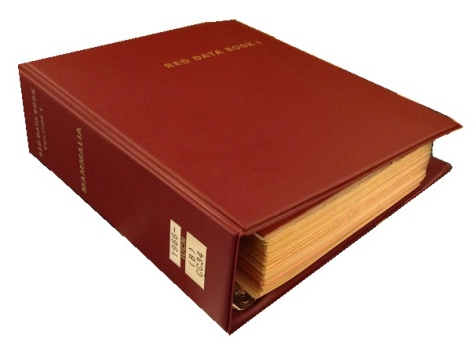

The listing of rare creatures is an old activity. However, in the 1960s the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) began compiling and publishing its Red Data Books of threatened species, starting with two volumes, Mammalia (mammals) and Aves (birds). I’ve described these ring-bound collections elsewhere as the ‘rarest important books of the twentieth century’ (ironically, about rarity), since, as far as I can tell, no pristine first editions exist. The reason for this is simple: the books contained instructions for their own partial destruction: as new knowledge of the state of rarity was available, so old sheets of data were discarded.

Since the 1960s red data lists have proliferated – there are international and many national versions – and grown in influence. Inclusion in the list (or not) could be critical for the survival of a species. The criteria for inclusion however were largely qualitative, and rested on the judgement of experts. An ‘endangered’ mammal in the original volume, for example, was defined as one in ‘immediate danger of extinction: continued survival unlikely without the implementation of special protective measures’. But how immediate was immediate enough? How, precisely, unlikely was ‘unlikely’?

For a time these vagaries did not seem to matter. But in the late 1980s and 1990s these definitions were replaced, after much negotiation and fierce debate, by much more detailed, quantitative criteria that appealed to measures of probabilities drawn from conservation biology of populations. These quantitative criteria are not only now used for determining the IUCN red data lists, but criteria modelled on them are also seen as relevant to the operation of CITES, the international agreement that restricts trade in endangered species. The criteria therefore are not only foundational for conservation but also shape how rare plants and animals enter the world economy. You can see examples of the new quantitative criteria here (IUCN) and, in partial, compromised form, here (CITES).

The criteria were largely the work of Georgina Mace, who is now Professor of Biodiversity and Ecosystems at UCL, but in 1989 was working at the Institute of Zoology in London. The Species Survival Commission of IUCN invited Mace to ‘undertake the important task of preparing a concept discussion document on the Red Data Book categories with a view to their reformulation’. Successive drafts of new categories were shown to a widening network of conservation biologists and practitioners. Russell Lande, a member of the Department of Ecology and Evolution at the University of Chicago, who had experience applying population viability analysis in the highly controversial case of the northern spotted owl (the conservation of which ran against logging interests), joined the project. The academic statement of the new approach, a paper authored by Mace and Lande, was published in Conservation Biology in 1991. The “Mace-Lande criteria” were then debated and tested under intense scrutiny as measures of level of extinction threat in global conservation governance.

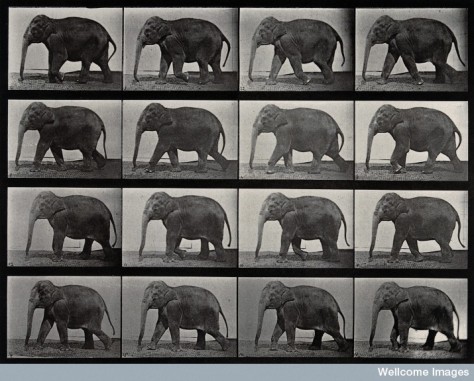

Reading the responses to the new criteria, what is fascinating is the range of views revealed: the criteria were proposed as ‘objective’ but respondents take issue with the achievement, desirability or need for objectivity; some see the intensive population studies as the best way to secure conservation because robust statements about levels of threat could be made, while others saw them as expensive, perhaps only affordable by rich countries; others still disputed the approach because it might work well for mammals (especially the charismatic megafauna for which generous funds for research were available) but presented practical and even philosophical problems for insects or plants. Many saw the use of percentages as evidence of precision and as sound grounds for policy making; but others worried that talk of probabilities suggested uncertainties that the developers’ lawyers would exploit.

The debates over the criteria provide a superbly rich case study for following the advantages and disadvantages of appealing to numbers when attempting to solve major global problems. I am tracing these discussions at the primary source level, and the picture that is emerging is, I think, an important one. It is ongoing, and if you want to know more then please contact me at jonathan.agar@ucl.ac.uk.